By Naomi Grimley

Global affairs correspondent

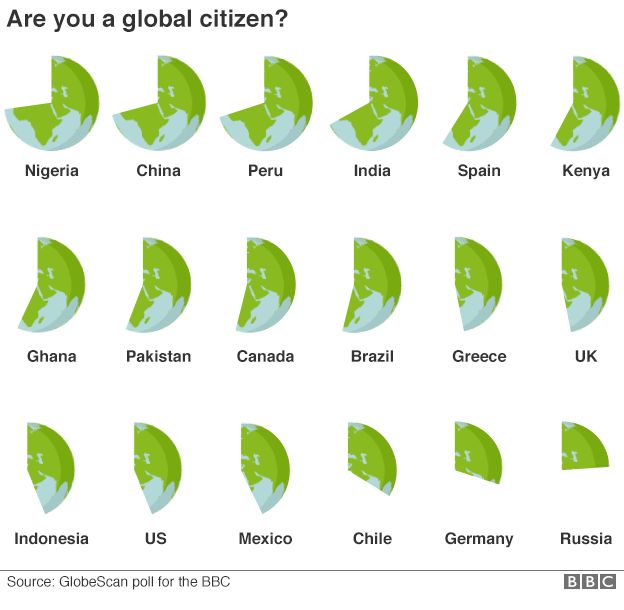

People are increasingly identifying themselves as global rather than national citizens, according to a BBC World Service poll.

The

trend is particularly marked in emerging economies, where people see

themselves as outward looking and internationally minded.However, in Germany fewer people say they feel like global citizens now, compared with 2001.

Pollsters GlobeScan questioned more than 20,000 people in 18 countries.

More than half of those asked (56%) in emerging economies saw themselves first and foremost as global citizens rather than national citizens.

In Nigeria (73%), China (71%), Peru (70%) and India (67%) the data is particularly marked.

By contrast, the trend in the industrialised nations seems to be heading in the opposite direction.

In these richer nations, the concept of global citizenship appears to have taken a serious hit after the financial crash of 2008. In Germany, for example, only 30% of respondents see themselves as global citizens.

According to Lionel Bellier from GlobeScan, this is the lowest proportion seen in Germany since the poll began 15 years ago.

"It has to be seen in the context of a very charged environment, politically and emotionally, following Angela Merkel's policy to open the doors to a million refugees last year."

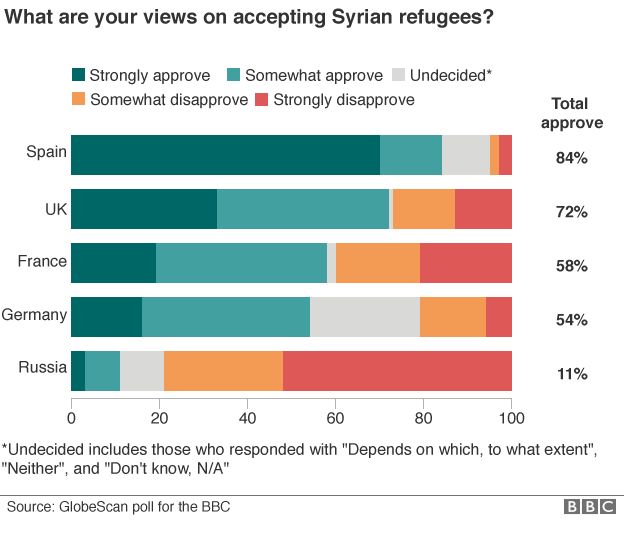

The poll suggests a degree of soul-searching in Germany about how open its doors should be in the future.

It says 54% of German respondents approved of welcoming Syrians to their country. In the UK, where the government has resolutely capped the number of Syrian refugees, the figure was much higher at 72%.

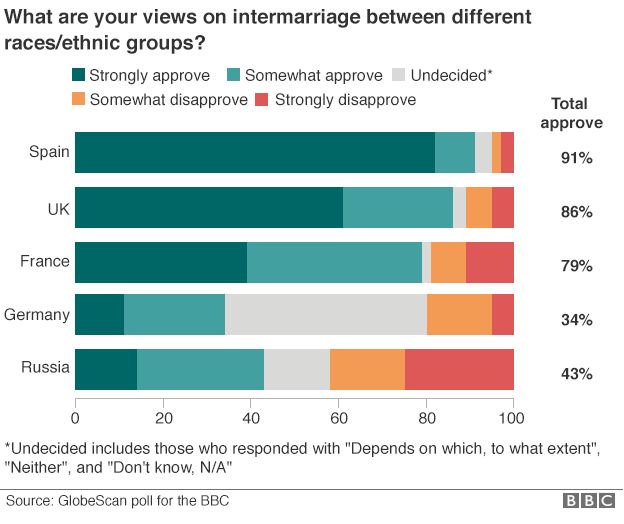

A significant proportion of Germans also sat on the fence when they were asked about issues to do with immigration and society.

On the question of whether intermarriage was a welcome development, for example, 46% of German respondents were not sure how to respond or they tried to qualify their answers by saying it depended what the circumstances were.

This is in stark contrast to other European countries, such as France, where people were much more emphatically in favour of marriages between people from different racial or religious backgrounds.

These grey areas on the bar charts could suggest Germany is still grappling with whether it wants to welcome newcomers or not.

"There is a lot of uncertainty there," says Mr Bellier.

"German respondents are showing a high level of indecisiveness when they are asked if they approve or disapprove of these developments and whether they accept the fact that their country is taking a lead on refugees."

According to the data, there are some clear divides in attitudes within continents.

In Europe, it is Russia which has the strongest resistance to intermarriage, with 43% of Russians actively disapproving of marriages between different races and ethnic groups.

Compare that with Spain, where only 5% would be opposed to such matches. Spain also noticeably has the most respondents who see themselves as global citizens

Russia appears to have the strongest overall opposition to immigration. Only 11% of the Russians polled would approve of accepting refugees from Syria, for example.

On the other hand, Spain would be the most welcoming of all the countries polled when it comes to receiving refugees from the Syrian conflict. There, an eye-catching majority - 84% - believe they should take in more of those fleeing the five-year civil war.

The figures suggest there is also an interesting divide emerging in North American attitudes to refugees. Of those Canadians asked, 77% said they would approve of accepting Syrians fleeing their home country. But in the United States that figure drops to 55%.

Indonesia has the weakest sense of national citizenship (4%). Instead, it seems Indonesians have a much stronger sense of localism, with over half of respondents seeing their immediate communities as the most important way of defining themselves.

In general, religion plays a much smaller part how people define themselves compared to nationality. The big exception to that rule is Pakistan, with 43% of Pakistanis appearing to identify themselves first and foremost by their religion - considerably higher than any other country.

The polling on religion also reminds us of one of the defining differences between old-world Europe and the United States. In the US, 15% of those asked would who define themselves first and foremost by religion. In European countries that figure is only 5%.

What is 'global citizenship' anyway?

One problem with polling attitudes on identity is that "global citizenship" is a difficult concept to define and the poll left it open to those taking part to interpret.For some, it might be about the projection of economic clout across the world. To others, it might mean an altruistic impulse to tackle the world's problems in a spirit of togetherness - whether that is climate change or inequality in the developing world.

Global citizenship might also be about ease of communication in an interconnected age and being able to have a voice on social media.

And for many, it will be about migration and mobility. We are, after all, witnessing the biggest movements of people since the World War Two.

This is not just driven by war and conflict. It is also because the world as a whole is becoming more prosperous and air travel is becoming more affordable to the rising middle classes.

No comments:

Post a Comment